I first met Teacher S over Zoom the year my district went 95% virtual and leadership rolled out a new instructional model for ESOL students (back then, they were still called ESOL students, instead of the alphabet soup of acronyms we use today). Under the extreme circumstances of the pandemic, it was a pleasure to interact professionally with another teacher regularly. Mostly I followed along and did pull-out groups in the Breakout room, where I could provide additional language support. I enjoyed the camaraderie of having someone to help me figure out this totally new way of teaching.

Once back in the building, co-teaching took on a different tone. Instead of equal-size Zoom boxes, one of us now had a classroom and one of us didn’t. Teacher S filled the shelves with their books and knick-knacks, the walls with their colorful posters, and rugs and furniture brought in from their house. I had a shared desk in a shared office in the ESOL Department (now called the ELD office = English Language Development).

Only one teacher’s name appeared on the electronic gradebook and the Canvas classroom tile. That teacher received all communication from parents, counselors, and the Main Office. I was lucky if they remembered to share pertinent information about students, new policies or schedule changes. I’d been erased.

All the ELD teachers were plugging in to the content teachers’ classes, no matter their level of experience, expertise, or comfort level. That first year, I had five different co-teachers. I had to lug my cart through the hallways, moving from room to room to room, struggling to get past clusters of students before the next bell rang.

With each teacher, I had to negotiate the space – who would stand where, who would deliver the lessons, where would I put my things? With each teacher, I had to negotiate who would prepare which lessons, who would deliver the lessons, and who would grade the student work. I had to tread carefully with each teacher, giving advance warning that I was an interrupter, and would that be okay? Sometimes I would need to paraphrase, repeat, or clarify information for ELD students. Sometimes I would need to modify handouts so the students learning English could understand what they were reading. Each interaction was a careful conversation.

Today, that’s pretty much how co-teaching runs for secondary ELD teachers in MCPS. We’re thrown together with other teachers and it’s on us, the ELD teachers, to adapt to the content teacher’s style, their preferences, their classrooms. If we’re lucky, our ideas and teaching style mesh perfectly, and all the little decisions we make every day will help students thrive. If not, it’s a constant negotiation of every single interaction that takes place.

Diplomacy involves give and take – that I understand. But why does it always seem like the ELD specialist has to give something up?

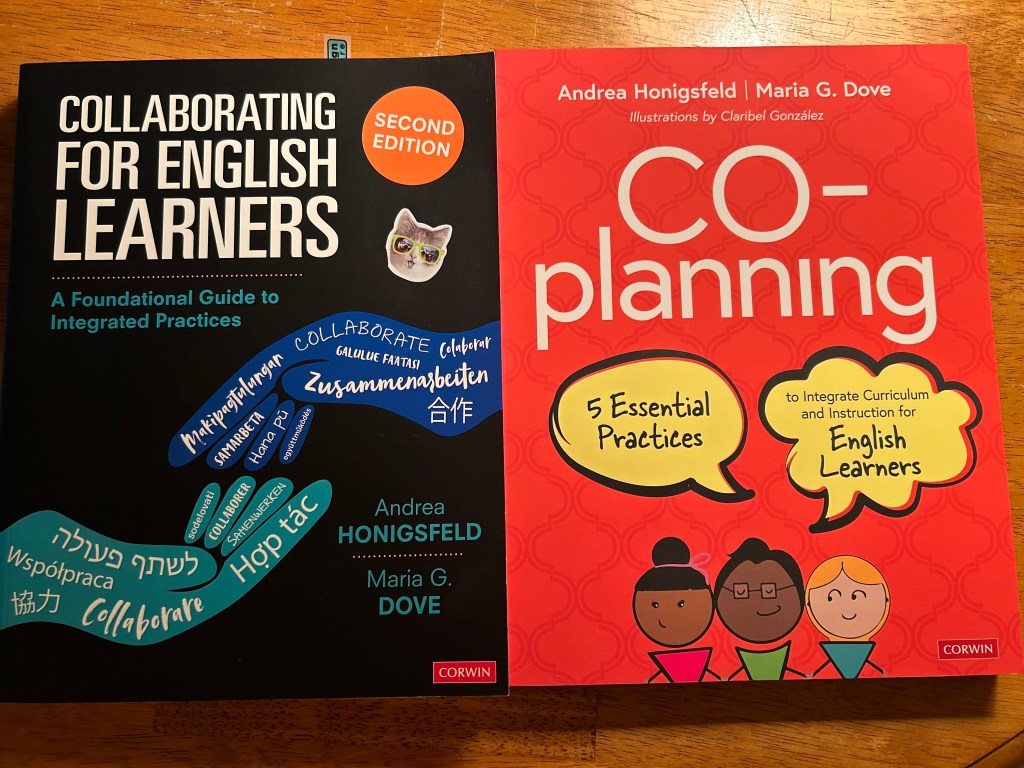

According to Collaborating for English Learners, by Andrea Honigsfeld and Maria G. Dove, teachers should “be on an equal footing” and all members of collaborative teams need “equal time to contribute to team efforts.”

In their updated book, Co-Planning to Integrate Instruction for English Learners (2022), the same authors write “Co-planning requires teachers to change not only what they do but also how they think.” This is a critically important comment. “For co-planning to work, teachers must endeavor to share their beliefs, understandings, opinions, and convictions with fellow teachers and be open to incorporating unfamiliar ideas into their class instruction.”

It takes a certain type of professional to be flexible enough to incorporate unfamiliar ideas into their instruction. Most teachers are control freaks. Most teachers are used to being the lone voice of authority in front of children. Most are not willing to cede any territory without a fight. Or at least an exhausting series of conversations.

It’s only the third week of school, and I’ve been doing the dance of diplomacy since Pre-Service Week. I’m tired. I’ve lost my temper with my co-teachers; I’ve gotten on their nerves. I’ve succeeded in some important ways, and I’ve caved on others.

Once the students enter the room, we smile and carry on.