I couldn’t do it. The job of a high school administrator is unrelenting and thankless.

Sure, teaching is a super challenging profession. But teachers get to build relationships with students, we get the rewards of watching their eyes grow wide with aha! moments. We get to help them with after-school activities and college applications. At the end of the year, we receive hugs and thank-you notes.

Administrators are the real heroes of a school.

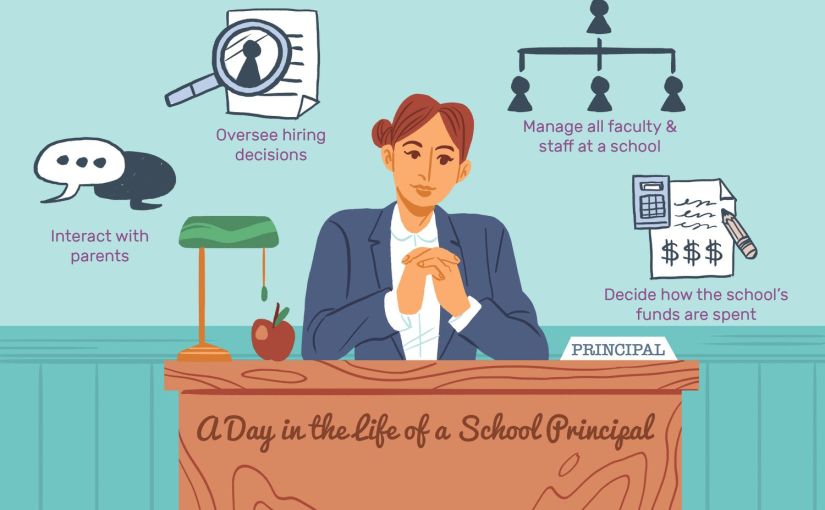

They set the tone with their policies, procedures, and presence. Administrators deal with district bureaucracy, angry parents, underperforming teachers, and troublemaker students. They deal with the cafeteria, cleaning staff, bus transportation, athletic fields, and finances. They observe teachers and write formal evaluations. On top of that, high school principals and assistant principals supervise every football game, school play, and special activity. Everyone blames them when something goes wrong or they’re unhappy with a situation.

My principal shares her praise for school teams regularly on social media. She’s everywhere all the time with something positive to say. Even with an excellent leadership team, the job is alarmingly stressful. It’s no wonder that three MCPS high school principals are retiring in the middle of the school year (Clarksburg,Seneca Valley, and Walter Johnson).

During the month of October, ten different bomb threats disrupted our schools, causing fear and chaos. Rapid admin response can save lives. We learned later that seven of those bomb threats were called in by a 12-year-old boy. School principals quickly communicated to the community via social media and email. Yet, people criticized their slow communication and response. I cannot imagine herding 3,000 students into a stadium in an orderly manner.

At my high school, we had two major mental health crises that disrupted teaching and learning last month – one occurred on the Friday of Spirit Week, when students were scheduled to attend a pep rally in the stadium at the end of the day. Instead of cheering for the homecoming team, we went into lock down until the bell rang, after an ambulance had quietly hauled the student away.

This week, a student brought a loaded gun to school. Administrators and police handled it effectively before teachers or staff even knew that anything was going on. At the end of the day, the principal invited us to a meeting in the cafeteria to explain what happened. We are so fortunate to have excellent leadership at my school, but teachers and parents still complain.

As one of the elected Building Representatives for MCEA, the teachers’ union, I helped craft a school climate survey sent to our 200 members. Despite our focus on “shared responsibility” very few staff responded, but the ones who did complained that “administrators need to be present in the hallways” and “we need better communication.”

I teach at one of the largest high schools in the state of Maryland. We have one principal and three assistant principals, plus a handful of staff in leadership roles with walkie-talkies. How is it possible for six or seven people to supervise the hallways while dealing with all the crap they deal with every day? And those are just the situations that I know about.

Schools have the responsibility of dealing with all of society’s ills, but so many of us feel completely unprepared. I stand in the hall and brightly encourage wandering students to get to class. If I speak using the wrong tone, a dysregulated kid could turn their rage on me. Then what? We need each other’s support – teachers, parents, students, and administrators.

My admin team is doing a great job and they deserve our thanks. I could never do that job! Now get to class! The bell just rang!